Can teams work like gears?

Introducing a Flexible Framework for Modern Product Development

When the field of UX was developing in the late 2010s, there was heavy emphasis on design thinking and “process.” Schools and bootcamps taught it, employers wanted you to demonstrate it, and teams pushed for it to drive innovation.

Yet as companies rushed to build Product and Design teams, the rules of “the process” were never really universally agreed upon. What emerged instead was a confusing mush of design-guided thinking wrapped in corporate red tape. What was meant to unlock creativity, ended up flushing it away.

When I entered the field, I learned Stanford's Design Thinking Process, the Double Diamond, NN/g's Design Thinking and IBM's Design Loop. These design frameworks all offered strong guidance on the steps a design team should take to develop an idea, but these frameworks always collapsed on the job site.

Why? Because developing software requires collaboration with other teams like Product, Research, and Engineering—each following their own frameworks and workflows. The problem is that these frameworks are typically designed in isolation. So when these workflows inevitably intersect, they don’t gently flow into each other, they crash!

This unresolved interdependency often results in a variety of issues:

Product teams that define UX problems before understanding their users

Research that confirms decisions rather than informs them

Design work that’s disconnected from technical realities

and handoffs that feel like a messy exchange of fragmented ideas rather than a smooth delivery of accumulated knowledge

Multiply this with things like employee turnover, tight deadlines, and limited budgets and resources, and companies end up with their unique patchwork “process” shaped by their own culture and constraints.

These aren't growing pains of the maturing field of design — they're structural failures in how we approach product development.

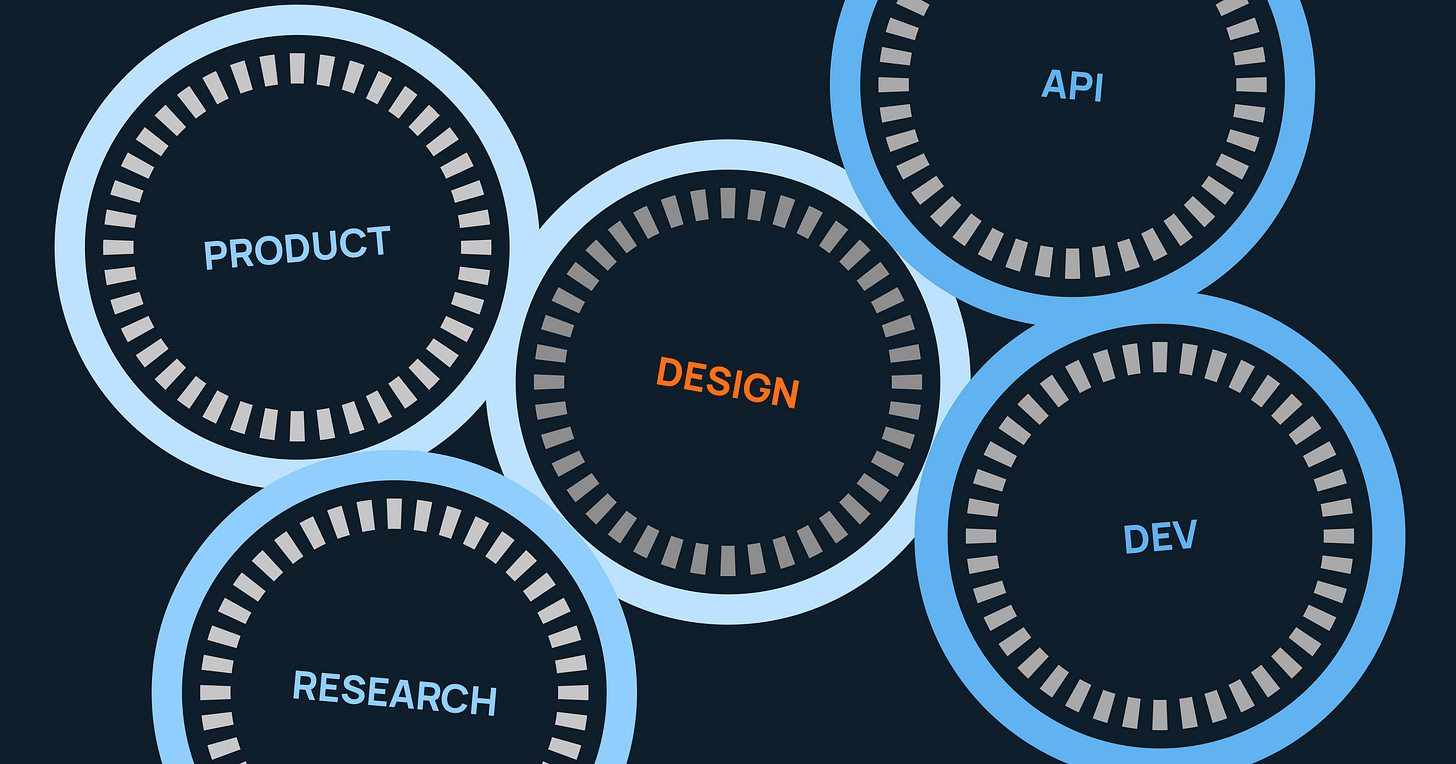

Different teams have different rhythms

In a product development environment, there’s a basic truth: everyone has a different rhythm, expertise, and need.

Embracing the distinct operating characteristics of Product, Research, Design and Engineering will allow each group to apply their domain expertise and help the entire group maximize their collective knowledge. When we refine the connection points between these groups is when see improvements in how the full group brings products from idea to reality.

Think about a classic wristwatch. Inside are different sized gears moving at different speeds. Some make quick, tiny ticks while others make big, slow turns. But they all work in unison to tell time.

This is possible because each gear has a job. They connect at specific points and transfer energy to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Product Development teams work the same way. Each department has its own expertise and way of working. The magic happens when they connect at the right moments to move the system towards its goal.

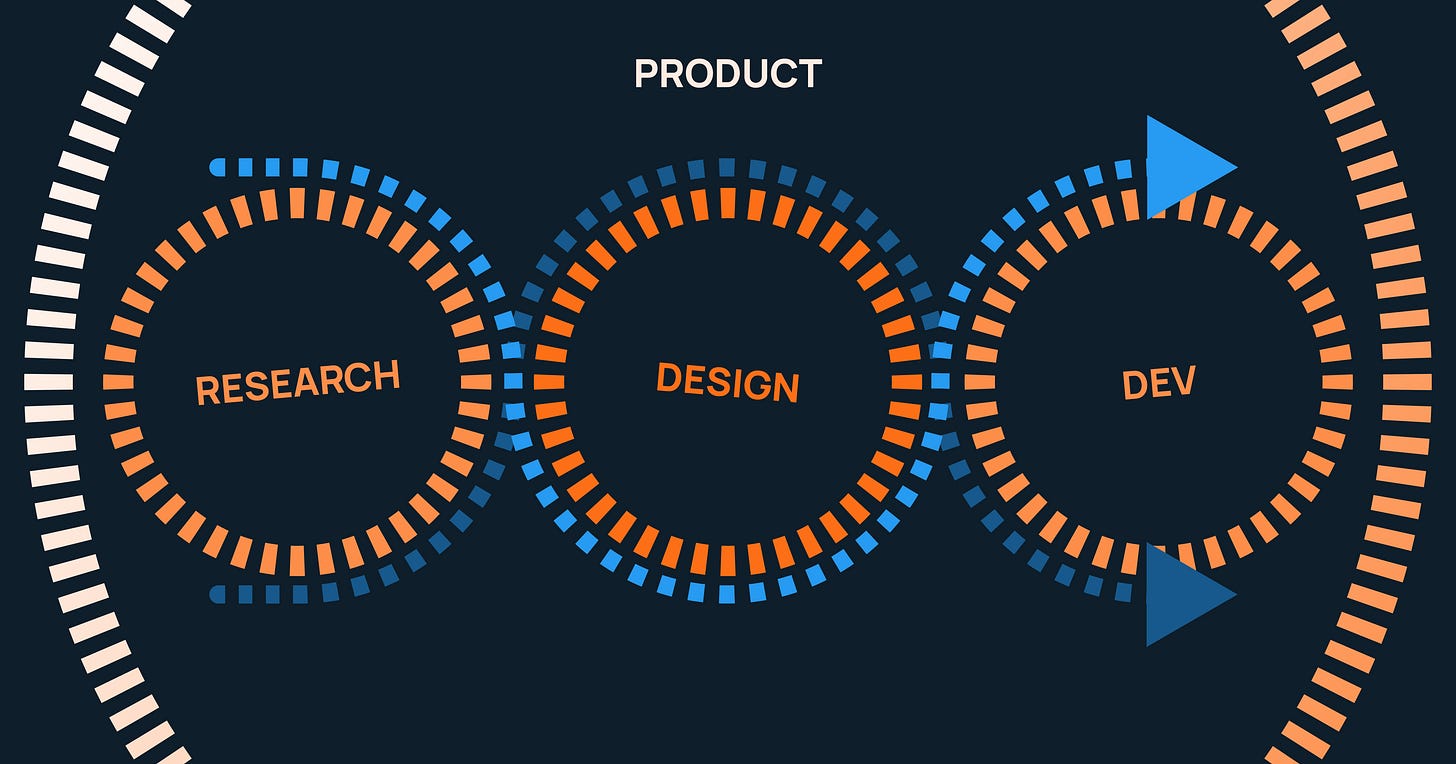

Gears are meant to turn each other

In the Gears framework, each department has its own unique workflow cycle — called a gear. As the team completes their tasks, the gear turns and eventually arrives at a connection point, to align with the departments.

These connection points are the critical moments where one team's work becomes another team's starting point.

At the connection point is where:

Teams share work that others can build upon—whether that's research insights, design specifications, or code

Everyone understands exactly what information they need to provide to the next team

Key decisions and their rationales are documented

Teams hold each other accountable for maintaining momentum

These connection points are the teeth of the gears. As one department’s gear turns, it also turns the connecting department’s gear at the right moment and with the right information.

By focusing on these connection points rather than prescribing specific internal methods, it allows each team to work in the way that best suits their strengths and expertise while ensuring the gears turns smoothly to accomplish the collective goal.

Adaptability empowers teams

Gears was developed at Khaos to keep our workflows light and flexible, but adaptive for scale. It offers a way to maintain the specialized excellence that comes from letting experts be experts, while keeping the necessary connections to efficiently build products.

It adapts to the needs of the team, because:

Not every project needs all gears to turn (sometimes you just need research or a quick design update)

Teams often work in parallel, not just one after another

Different projects need different rhythms and pacing

a gear may need several rotations to get something right before the next team can start, and that’s okay

This flexibility lets you adapt to what the work actually needs instead of forcing it into a one-size-fits-all approach.

The important thing to remember is that the Gears framework is not a process. It's simply the structure that guides your process. However way you work between the connection points is the right way.

In upcoming articles, I'll dive deeper into each gear and the connection points that make them run. I’'ll discuss implementation strategies at Khaos and offer templates that helped me adapt Gears in my organization.